The zombification of Corporate America

Over the past three weeks, there’s been a lot of discussion of duration-related mark-to-market losses, depositor flight, money market strains, and government interventions pertaining to the banking sector. What I haven’t seen a lot of discussion on is the traditional cause of banking crises: people or firms who borrow money from banks in good times and then find they can’t repay their debts in harder times, also known as loan losses or defaults.

My feeling is that we will see a sharp rise in loan losses as well as defaults on other types of debt before this economic cycle is over. I think there are some in the market who agree with this view, including most of the potential acquirers of Silicon Valley Bank’s loan book. Consider that even though the FDIC was able to find a buyer for SVB’s securities assets pretty quickly (the proximate cause of SVB’s failure), it has taken two weeks to find a buyer for the rest of SVB’s loan portfolio, and it looks like the FDIC was forced to guarantee that purchase. As I mentioned in my previous note, I think this is because the market realizes that SVB’s $74 billion loan book is not worth close to $74 billion (a big chunk of the people/firms that borrowed that $74 billion are not going to pay it back). The FDIC has probably offered to make the acquirer whole on any money they lose from this deal.

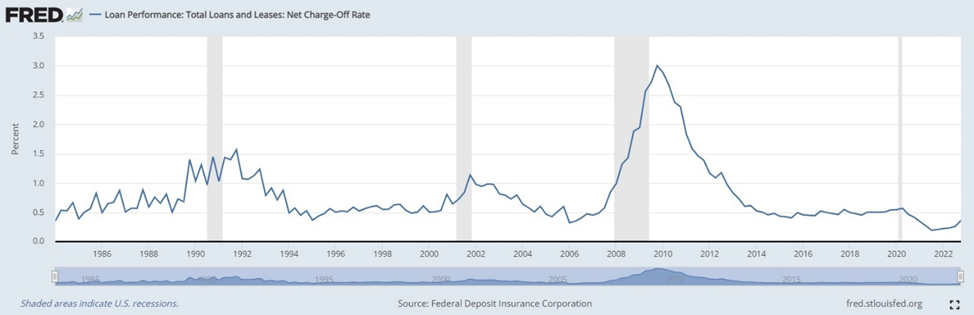

Because history repeats itself, especially in financial markets, I like to look for patterns in historical data. So I started by looking at historical loan loss data to see where we currently are in the cycle:

Nice! So in the post-COVID era, we have seen the best performance of bank loan books since… 1984. Even a mild recession like the 2001 tech crash implies a rate of loan losses 3x higher than what we have right now.

Why bank loan losses don’t worry me from a systemic perspective, but they do from a shareholder returns perspective

Despite the above chart, I am not super worried about the banking sector’s loan losses causing a giant cascade failure. I think the biggest problems lie elsewhere. Shareholder returns are going to get crushed but I don’t think there will be a zombie apocalypse here. There’s a few reasons for this:

1) Just because a borrower defaults on a loan doesn’t mean that the bank loses all of its value. Some loans will “cure,” meaning the borrower will recover from temporary financial hardship and start paying again. Other borrowers who reach bankruptcy may have enough assets to still pay back many debts, at least partially. For example, this paper suggests that in commercial real estate, lenders can expect recoveries on defaulted loans to be around 50% or better. From my time as a municipal bond analyst, I remember municipal bankruptcies resulting in recovery rates of 80% or better for investors.

2) The U.S. banking sector is well-capitalized, and the amount of loan losses has to be compared to the capital available to absorb those losses. Total equity capital in the U.S. banking sector was $2.2 trillion against an asset base of $23.6 trillion, or about 9%. For reference, this number was 5% in 1984.

3) Looking specifically at loan losses, the total loan and lease book in the U.S. is $12 trillion. Assuming the annual loan loss rate reaches ~1% as it did in 2001, and assuming the doldrums last for three years, that’s total loan losses of $360 billion ($12T * 1% * 3 years) against a capital base of $2.2 trillion. That’s a destruction of 16% ($360bn / $2200bn) of U.S. bank capital, which is a lot, but the point of equity is to absorb losses. Huge numbers of banks won’t fail from this, I believe (caveat: I still need to do a deep dive on how bad the disaster in CRE is going to be. I reserve the right to come back and revise this sentence based on that analysis.) Regulators will force undercapitalized banks to raise fresh capital in a harsh market environment, to the detriment of shareholders, but it won’t be fatal to the banks themselves.

4) Of course, I’m not counting the unrealized losses in the securities portfolios of these banks. However, the Fed’s new Bank Term Funding Program allows banks to paper over these unrealized losses indefinitely at a price of ~3% of their par value per year if needed.

5) Caveat #2 – I don’t what to think about deposit flight to money market funds from a systemic risk perspective. In a nutshell, this is just a description of the phenomenon where Bank of America pays me 0% interest in my account but I can easily move money into a Fidelity money market settlement fund and get 4%+. All else equal, this should raise bank costs and depress profits as banks fight to retain deposits by offering higher savings rates.

In sum, loan losses, forced capital raises, higher deposit costs and papering over unrealized losses on securities will badly damage shareholder returns over the next 10 years, but they won’t sink the U.S. banking sector in the aggregate. Bank stock prices will fall sharply as the market prices these factors in. Some banks will fail, but they won’t all fail.

What about monies owed to entities other than banks?

The U.S. is different from other advanced industrialized economies like Europe and Japan in that the banking sector plays a relatively smaller role in providing capital to the economy than it does in other regions.[1],[2],[3] One strength of the U.S. economy, in my view, is that we have extremely well-developed “capital markets” where companies and in some ways even individuals can raise funds directly without relying on banks as intermediaries. The phrase “capital market” should be interpreted literally. It’s exactly what it sounds like—a free market where people can buy and sell capital. If a company needs to raise capital for growth, like building a factory, it has 1) the option of borrowing that money from a bank or 2) directly selling new shares and bonds to the public to get those funds.

What does this mean in terms of trying to understand where hidden breaking points might lie? It means that I want to look beyond bank loan books and find out which other players have gotten themselves into trouble by using capital markets and bypassing the banking sector entirely. Most financial crises can be traced to entities who have borrowed too much money and can’t pay it back, whether to banks or someone else.

Economic downturn rule of thumb #1: Who has borrowed too much money and won’t be able to pay it back?

The good news: I don’t think it’s households.

2008 was different. Households entered that crisis carrying a lot of debt, borne out both by stories of douchebags in the mist[4] and by data:

Just some rough numbers on this—debt per capita was about $48,000 in the U.S. in 2007, and something like $57,000 per person in 2022. Although the total amount of household debt went up 30% from 2007, the population increased 10% or so in the same time frame. Moreover, the economy itself grew and inflation is a lot higher, so the $57,000 today feels like $40,000 in 2007 dollars.

With household debt down 20% relative to 2008, and a lot of the debt composed of fixed-rate payments on mortgages, I am satisfied saying this sector is mostly safe.

Who has borrowed too much money and won’t be able to pay it back: U.S. corporations edition

Ruling out households leaves two big sectors of the economy as potential culprits: the government and Corporate America.

The government has certainly borrowed way too much money but that’s going to get resolved in a different way (it’ll be a sustained period of high inflation, like 20+ years, but I’ll discuss government debt in a different post). Right now I want to talk about the corporate sector. Let’s start with a level set:

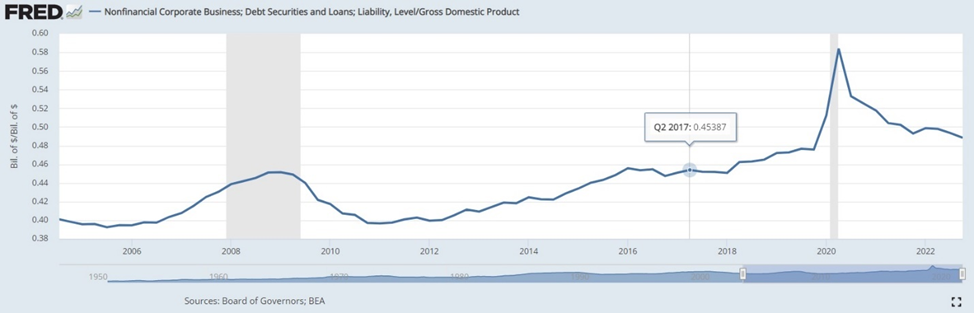

Over the same time frame as above, it looks like corporate indebtedness has gone from 41% of GDP to 49% or so, or an increase of about 20%. In absolute terms, corporate debt has increased from about $6 trillion in 2007 to about $12.7 trillion today.[5] I’ll repeat: if you’re looking for the next domino to fall, look for the people that are levered out the wazoo. This looks wazoo to me.

Why corporate leverage matters

When you are analyzing corporate balance sheets, a very broad indicator like “corporate debt to GDP” only suggests that corporate debt might be a place to look for problems—it doesn’t automatically mean that there is a problem. In order to definitively identify a problem, we need more than a suspicion—we need hard evidence. One harder piece of evidence is looking at corporate leverage ratios, which are simply metrics that help us understand how much debt is “too much debt.”

Why does “too much debt” matter in the first place? I think of debt as an amplifier for whatever underlying trend is present—it makes good times better, and bad times worse. Debt makes it harder for a person or entity to withstand shocks. Rather than being a shock absorber (like equity), it’s a shock amplifier. I’ll illustrate with an example:

Consider a simple example of you opening up a laundromat. You need to rent a space, buy washing machines, and hire staff. Let’s say you need $100,000 to do all that. You have a choice of borrowing money (debt) or selling ownership stakes in the company (equity) to raise those funds. In other words, you could borrow that $100k from a bank at let’s say 5%, or you could go to your friends and sell shares in your business for $100,000. How are these two paths different?

Now let’s consider a time of stress caused by an unanticipated shock—the city decides to dig up a broken sewer line underneath the road in front of your laundromat. Due to the road work, you lose 80% of your customers and are now cash-flow negative month-to-month due to your ongoing electricity, salary and rent expenses. If you were financed 100% with equity, you could suspend the dividend you normally pay to your shareholders until times improve and run down your cash balance to keep the lights on. But if you’re funded with debt, and you miss a single debt payment, the bank will take you to bankruptcy court and take over the entire business. In good, stable, predictable times, the bank debt might be better because you get to deduct the interest expense from your taxes and shareholders would typically demand higher percentage returns than the 5% the bank is charging you. But in bad times, you have the total freedom to stop all payments to shareholders without (legal) consequence, but if you stop paying the bank, you lose your business. (I’ll leave you to decide if the world is heading into a period of “good, stable, predictable” times or “not good, not stable, not predictable” times.)

A decade of stock buybacks and the hollowing out of corporate balance sheets

One phenomenon driven by the last 15 years of zero interest rates is the replacement of equity capital with debt capital on corporate balance sheets.[6] It’s easy to see the correlation by simply looking at the total increase in corporate debt, but I want to talk about one of the mechanics through which this has happened: stock buybacks.

A stock buyback is basically the opposite of an IPO. You have a share of Apple, trading at $100, and Apple comes to you and offers you $100 cash (or a slight premium) in exchange for your share. This transaction increases two of Apple’s leverage ratios—its debt-to-assets ratio and its debt-to-equity ratio. This trade doesn’t do anything to Apple’s debt directly, but intuitively, it reduces the amount of assets (cash) Apple has to cover its debt. To take an extreme example, if you were a bank that had loaned money to Apple and Apple did this trade with someone else using the last $100 of cash that it had, you would be pissed.[7]Debt-to-equity is the same. Let’s say Apple had assets of $1000 financed by $500 of debt and $500 of equity. After the above trade, it now has assets of $900 financed by $500 of debt and only $400 of equity. The debt-to-equity ratio went from 1:1 to 1.25:1.

The more dangerous version of this is using debt to fund stock buybacks. Let’s take the same example, except let’s say Apple didn’t have any cash. It has $1000 of assets financed by $500 of debt and $500 of equity. It goes to the bank and borrows $100 of cash, which it then uses to buy your share for $100. Its total assets haven’t changed, but it now has debt of $600 and equity of $400—a debt-to-equity ratio of 1.5:1. (The cynical explanation as to why companies do this is that it tends to pump stock prices in the short-to-medium term, which is a major factor in executive compensation.) I call this the “hollowing-out” of the balance sheet. A great deal of this has happened in the last 10 years.

Like most things in finance, in moderation, there are times and places where stock buybacks make a lot of sense. The problem with finance is that it’s driven in the short-term by investor psychology and in the long-term by math. In the short-term, investors have been known to… deviate from moderation.

Flying zombies: The Boeing Company

Since I’m not a stock analyst, I turned to ChatGPT for help on a bunch of questions related to corporate leverage and share buybacks. Specifically, I asked it which S&P 500 companies had the highest debt-to-asset ratios right now and which companies had done the most share buybacks since 2008. It came back with a bunch of tech and oil companies and also Boeing.

I didn’t expect to see Boeing there. I mean, it’s one of the biggest arms suppliers to the U.S. government and the only business better than selling weapons to the U.S. government is selling surveillance equipment to the Chinese government. Since current AI has a tendency to make things up, I went and looked at Boeing’s financial statements myself. What I found was… a hot pile of garbage.

Boeing has been losing money for the last four years. It also has book assets of $137 billion against liabilities of $152 billion, meaning the book value of equity in the company is -$15 billion. If this was a bank, regulators would have taken it out back and shot it a long time ago. It also spent $43 billion on stock buybacks in the decade leading up to 2020.[8] You might say that well, the reason it’s been operating at a loss the last 4 years is because of the 737 MAX debacle and the shutdown of the airline industry during COVID. Well, sure—the issues at SVB and Credit Suisse were also idiosyncratic. To me, stuff like the 737 MAX shenanigans are reminiscent of Archegos, Greensill and the bribery/money laundering issues at Credit Suisse—these are indications of weaknesses in the corporate culture.[9]

Regardless of what you think about the importance of corporate culture and leadership at the top, ultimately finance comes down to math in the long run, and this post is about the problems of corporate leverage. Boeing has about $12 billion of debt with interest rates between 1.17%-2.5% coming due by 2026. What rate is that debt going to be refinanced at? Even the ratings agencies[10](which are notoriously slow to the draw) have Boeing’s debt rated at barely above junk right now. As of right now, one corporate bond index shows yields of 5.5% on BBB debt.[11] Simply increasing the rate from 2% to 5.5%—a best-case scenario—on $12 billion of debt is an additional $420 million of annual interest expense, which is not something a company which is already losing $5 billion a year can really afford.

Is Boeing a zombie? I mean, it’s hard to call one of the largest suppliers to the U.S. defense budget a zombie. But looking at the numbers… Boeing is a zombie! At the very least, this is a company that is in the early stages of putrefaction, like a piece of chicken unearthed from the back of your fridge that has a greenish tint on it. Companies with strong balance sheets can withstand unexpected shocks. A company like Boeing, with a weak balance sheet plus idiosyncratic problems prior to an economic downturn, is likely to find itself in real trouble.

The stock market thinks Boeing is worth $120 billion. In theory, the value of any asset can be determined by calculating the present value[12]of all of the future cash flows it will produce in its lifetime (the value of a piece of farmland is equal to the present value of the selling price of all the wheat it will grow each year going forward). Now I’m sitting here looking at Boeing’s financials, and I’m asking myself, “what cash flows?”

This is a zombie, y’all. And there's more out there.

[1] For reference, U.S. GDP is $23 trillion and bank assets are roughly the same size. By contrast, German GDP is $4.2 trillion while its banking sector is $10.5 trillion. Japanese GDP is $5 trillion but its banking sector is nearly $20 trillion.

[2] The U.S. also has a very decentralized banking system compared to other advanced industrial nations. Unclear if this is a strength or a weakness—some people have called for the U.S. banking sector to have a lot more consolidation.

[3] One consequence of having both a relatively smaller and decentralized banking sector is that it’s much easier for us to let banks fail.

[4] This is one of my favorite articles about the psychology that preceded the 2008 crash. If you haven’t come across it before you must read it.

[5] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BCNSDODNS

[6] This is not a new idea—a Google search for “stock buybacks financed by debt” returned this, this and this.

[7] In real estate and project finance deals, banks lay down very strict rules on when developers are allowed to pay out cash to investors. Debt holders are way more lax with public companies—maybe because the holders of corporate debt are disaggregated and diffuse.

[8] https://www.newsweek.com/boeing-airlines-under-fire-90-billion-share-buybacks-stoke-controversy-bailout-pleas-least-1493934

[9] We taught a case study on the Boeing 737 MAX in our Beyond Behavioral Economics course. If folks are interested, I can provide that case and a bunch of references.

[10] https://www.fitchratings.com/entity/the-boeing-company-80090948

[11] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BAMLC0A4CBBBEY

[12] What discount rate are investors using to get to a present value of $120 billion?