Two weeks of bank failures and government interventions: the big picture

In the past two weeks, we’ve seen the closure or rescue of four banks: Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, First Republic Bank, and Credit Suisse. We’ve also seen large-scale interventions from central banks, in the form of the Fed’s new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) and the Swiss National Bank’s extension of CHF 100 billion in liquidity to Credit Suisse and its acquirer, UBS. These are extraordinary unusual events. In this note I lay out what I see as the common underlying themes and big-picture implications.

When interest rates go up, things break

There’s a simple explanation for the recent spate of chaos we’ve seen in financial markets: rising interest rates. There’s a relationship between interest rates and asset prices—when rates go up, asset prices go down. This is most evident in bond prices[1], but is also true for homes, company shares (and companies), and anything else that generates (or consumes) a cash flow.

The Fed has kept the benchmark U.S. interest rate at 0% for most of the last 15 years, beginning in December 2008. There was a shallow rate hiking cycle where the Fed raised interest rates by 2.25% over close to four years (December 2015-July 2019), but then the Fed started to cut again and returned to zero during the pandemic. Relative to history, this was an unusually long period of “easy money,” and people got used to it.

Due to the onset of high inflation after COVID, the Fed hiked interest rates by 4.5% in less than one year, beginning in March 2022. Markets have been accustomed to accommodative financial conditions for a very long time, and when those conditions change, market actors may not have adequately prepared for the new regime of restrictive financial conditions. One example of that has been the slow-motion meltdown in the tech/VC space over the past 18 months. Throwing money at negative cash flow startups may have looked attractive in an environment of 0% interest rates, but now that anyone can get 5% on their money by parking cash in a money market mutual fund, investors are suddenly reluctant to write blank checks.

Things breaking Part One: asset-liability mismatches

So some Accounting 101 here. Beginning in the 13thcentury,[2]we began to use a system of accounting called “double-entry bookkeeping.” One fundamental rule of double-entry bookkeeping is that assets must equal liabilities plus equity (A=L+E).

Assets are things you own. Liabilities are things you owe. Equity is the gap between the two. If I own a house worth $500,000, and I owe a $400,000 mortgage on the house, my equity in the house is $100,000. (If that house falls in value to $300,000, and I still owe $400,000 on the mortgage, I am “underwater,” meaning I have negative equity of -$100,000 in the house. This happened to a lot of people in 2008.)

This is simple enough to understand. Where things start to get complicated is when interest rates change. As I mentioned above, when interest rates go up, asset prices go down. The value of liabilities may also change, but not at the same rate as the change in assets. How sensitive your assets (or your liabilities) are to changes in interest rates is described by a mathematical concept called “duration.”[3]

As I described in my previous note on Silicon Valley Bank, SVB got killed based on asset-liability mismatch going against them while having a deposit base with 1) very high amounts of uninsured funds that was 2) particularly prone to viral herd behavior. SVB’s assets included a lot of “long-duration” bonds (meaning they were highly sensitive to changes in interest rates) matched against zero duration liabilities (deposits). When rates went up, the value of SVB’s assets fell, but the value of their liabilities ($ owed to depositors) didn’t change. This made them insolvent or close to insolvent, which sparked a bank run, which they didn’t have the liquidity to meet (insolvency led to them becoming illiquid).

How does relate to the other banks—Signature Bank, First Republic, and Credit Suisse?

Let me start by saying I know next to nothing about Signature Bank. My understanding is that it had heavy exposure to crypto (according to Wikipedia, 30% of deposits were crypto-related by 2021) and that it was being investigated by the DOJ for something relating to money laundering (unsure if this was related to crypto—but let’s be honest, it probably was). It failed a few days after SVB and another crypto-friendly bank called Silvergate failed. I’ll only say that the failure of banks heavily exposed to crypto doesn’t surprise me given the meltdown of the space in 2022. If a bank has made a lot of loans to crypto firms, and those firms collapse, it follows logically that the bank’s assets have lost a lot of value, but for a different reason than high duration.

First Republic Bank hasn’t failed or been put into receivership. From what I can tell, it’s a milder version of SVB, with the main similarity being that it has a relatively high amount of uninsured deposits[4](it caters to rich people on the coasts). Looking at their 2022 annual report, they only had ~$32 billion of bonds on an asset base of $212 billion. Even if all those bonds were long duration and were down 20%, that would mean $6 billion of losses against an equity base of $17 billion. Absorbing these kinds of losses is the point of equity. The risk to First Republic is that rich people will decide that the bank is in danger and pull deposits en masse, rather than asset-liability mismanagement or fraud at the bank. In this sense, First Republic’s issue is one of public confidence, which big players on Wall Street sought to bolster with a coordinated deposit of $30 billion in uninsured deposits last week (the opposite of a bank run). This was not a government intervention but may have been organized behind the scenes by the Fed.

Looking at these two cases, they have some things in common with SVB but not everything. Signature was exposed to a shaky industry like SVB, and First Republic had a lot of uninsured deposits like SVB. But neither had a big mark-to-market, duration-induced asset price loss like SVB.

Well, what about Credit Suisse? Credit Suisse is an entirely different animal, but still follows from the notion that “rising interest rates will cause some things to break.”

Things breaking Part Two: zombie firms (and people, and banks)

Zombies are people who should be dead but are somehow still ambulatory, not quite alive but not quite dead (un-dead). This descriptor can also be applied to firms. In mythology, zombies are creating using magic like voodoo. In the real world, zombies are created using magic like zero interest rates.

One definition of a zombie company is a firm that either doesn’t have enough operating profit to cover its debt service, or only has enough profit to cover debt service but not enough to pay down principal so it's barely keeping its head above water. It covers payments on existing debt by borrowing more money (something that’s easier to do when interest rates are very low). As an analogy, consider this example: you have a mortgage, but you don’t have enough salary to meet both the mortgage payments and living expenses. In order to avoid defaulting on your mortgage, you take out more debt, perhaps in the form of credit card balances or personal loans from friends and family. But you still have the basic problem of a mismatch between income and expenses, and you’re just digging yourself deeper into the hole. Alternately, you make enough money to cover interest payments but never enough to start paying down your debt principal. This makes you a financial zombie. Individuals can survive for a while in this condition, and firms even longer—provided fresh debt is available at low rates.

All of this goes out the window when interest rates go up. Not only are your debt payments likely to rise faster than your profits, but the shift in the interest rate regime might prompt lenders to take a second look at the wisdom of lending more money to you. Once you can’t cover your debt payments, you have to declare bankruptcy—the zombie put to death.

The rotting corpse of Credit Suisse stinking up financial markets

CS may not meet the technical definition of a zombie bank above, but I am still comfortable calling it a zombie. It’s been widely accepted on Wall Street for a decade that Credit Suisse is among the most poorly-run and mismanaged global banks out there, and maybe the worst. Here’s the market’s opinion on Credit Suisse’s quality as a firm, reflected in its stock price over the last 30 years:

Note the steady deterioration following 2008, even after the immediate panic of the 2008 crisis had been resolved, and during a period when the stock prices of other companies were on a tear, buoyed by the zero-rate environment. Over this period, Credit Suisse suffered from a number of self-inflicted scandals. From the Washington Post[5]: “Credit Suisse's failings included a criminal conviction for allowing drug dealers to launder money in Bulgaria, entanglement in a Mozambique corruption case, a spying scandal involving a former employee and an executive and a massive leak of client data to the media.” This doesn’t even cover the two biggest risk-management mistakes at Credit Suisse, which were the loss of $5.5 billion loaned to a hedge fund called Archegos Capital Management and $10 billion in the bankruptcy of Greensill Capital, both in 2021. Due to these losses, Credit Suisse has been operating in the red for the last two years. You might say that these are idiosyncratic events, but I’ll respond by saying that the reason CS’s operating profits don’t cover its expenses is because of a repeated pattern of internal risk management mistakes and a flawed corporate culture.

Firms can become zombies for different reasons, but the common thread between them is that rising interest rates will deliver them all to their final rest.

Pent-up bankruptcies and the zombies we don’t recognize

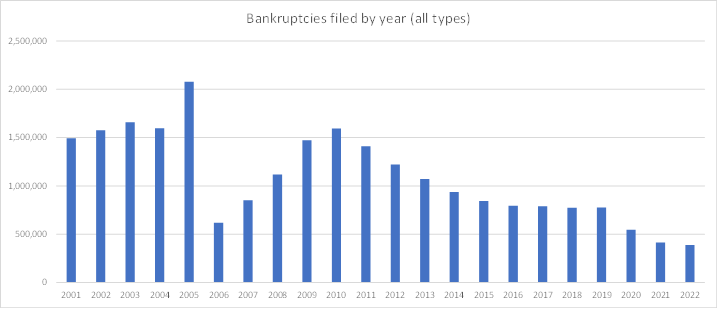

One symptom of an unusually long period of low rates:

What does this chart tell you? I’ll tell you what it tells me. I believe that firms, like people, have some natural rate of death. In normal times, some percentage of companies will die every year, either because of mismanagement, fraud, competition, or their products becoming obsolete. New firms will be born, just like people, in capitalism’s version of the cycle of life.

This chart tells me that whatever the natural rate of death of firms is, we’ve been below it for the last 10 years or so. In particular, the post-COVID government interventions—cutting rates, restarting QE, the emergency lending facilities (one of which I worked on at the Fed), the PPP, the stimulus checks—have suppressed a lot of deaths that should have happened in 2020, 2021, and 2022, not to mention whatever deaths were suppressed in the prior ten years. When we look back on this chart some time from now, I think the numbers for 2023, 2024, and 2025 will show 1,500,000+ bankruptcies. Restructuring lawyers are going to be busy for a while.

Was SVB a canary in the coal mine?

Yes, I do think that SVB’s failure is a portent of things to come. With that said, I don’t think there are many banks that have exactly the same problems as SVB, meaning a very large mark-to-market asset-liability duration mismatch combined with a flighty depositor base. Those were pre-existing underlying weaknesses that got exposed by rising rates. Other firms will have other weaknesses that will become obvious to everyone when exposed to the harsh light of higher interest rates.

Overall, though, I think the U.S. banking sector is in vastly better shape than it was in 2008. Just because a couple of larger banks failed does not mean the world is ending. Rising interest rates break things. But in my view, that’s a necessary evil as letting the number of zombies build up is worse.

I have more that I want to say about the wisdom of the policy response, moral hazard, expanding FDIC insurance limits, the Fed’s new lending facility, the profitability of the banking sector over the next ten years, where other zombies might be hiding, and more, but I’ll save all that for another note as I don’t want this thing to be 20 pages long.

[1]Here’s some intuition. Let’s say you bought a $100 bond yesterday that pays 3% interest. Today, the Fed hikes interest rates to 6%. How do you feel about owning a bond that pays 3% interest when market rates are at 6%? If you would like to give that bond back, that means you would rather have $100 than the bond, which means the price of the bond has fallen in your mind.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double-entry_bookkeeping

[3]“Duration” in bond math is not the same as time, but is related to time. A 30-year bond should have a longer duration than a 10-year bond, all else equal.

[4] https://www.fitchratings.com/research/banks/fitch-downgrades-first-republic-to-bb-places-ratings-on-negative-watch-15-03-2023

[5] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/03/20/credit-suisse-what-s-going-on-and-why-is-cs-stock-falling/07e3b6b6-c714-11ed-9cc5-a58a4f6d84cd_story.html#:~:text=1.-,What%20went%20wrong%3F,client%20data%20to%20the%20media.